Past Pluto

Past Pluto

Mason physicist’s research looks at the ends of the solar system

By Tara Laskowski, MFA ’06

Merav Opher was 7 years old when the spacecraft Voyager 1 launched in 1977. Now, 30 years later, Voyager 1 has traveled farther than any manmade object and is nudging its way to the edge of the solar system. Voyager 2 is only a few years behind.

And Opher, assistant professor of physics and astronomy, is the only female scientist—and by far one of the youngest scientists—working to calculate the flow of particles and magnetic fields of the area into which the spacecrafts are venturing.

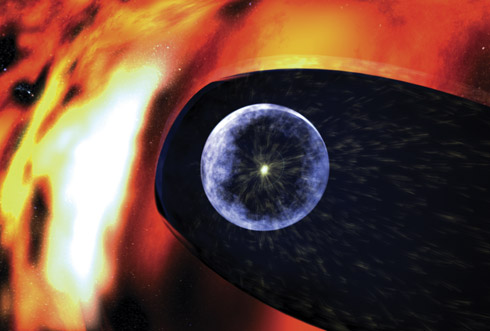

Many millions of miles past Pluto, the solar wind of our sun begins to lose its dominance when it comes in contact with the interstellar wind from the rest of our galaxy. Scientists consider the place where the two winds meet, the heliopause, to be the edge of our solar system, and Opher and her colleagues are eager to understand what happens in that area and beyond.

“We’re piercing a hole in the curtain that separates us from the rest of the galaxy. For the first time, we are looking to the outside, to what lies beyond us,” says Opher.

Opher has been working on calculations of the area since 2001, when she was a postdoctoral student with Paulett Liewer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. She adapted an advanced code developed by Tamas Gombosi at the University of Michigan to calculate the area the Voyager craft was approaching.

The findings were so exciting that Opher was eager to share them with Ed Stone, principal investigator of the entire Voyager mission.

Merav Opher

“He was just across the street, practically, working on the same thing I was interested in,” says Opher. “So one day I just called him up. I shared my results with him, blabbed on and on about the interesting things I was finding. Finally, he told me to come over and meet with him. That’s when we started working together.”

For Opher, it was an opportunity to work with one of her heroes.

“It took me a while to get comfortable with him. I had grown up watching him and listening to him talk about all the amazing discoveries Voyager was making.”

Although technology has dramatically improved since 1977, Voyager 1’s instruments still send back valuable data, and Opher and the rest of the Voyager team have been surprised at that data.

One of Opher’s most important discoveries is that the solar system is asymmetric. While scientists thought the northern and southern hemispheres would be similar, they have found that the southern hemisphere is more compressed. Even the eastern and western hemispheres don’t look the same.

“It’s a weird place,” admits Opher. “The physics is very different from anything we’ve ever seen.”

The team of scientists is also looking at how the magnetic fields change at the edge of the solar system. Scientists have believed that the magnetic field outside our solar system was parallel to the galactic plane, but Opher and her colleagues used two data sets to conclude that the magnetic field is actually 60 to 90 degrees perpendicular to the plane.

For the past several years, Opher’s research has taken off like a space shuttle. This year, she was awarded a National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER grant. The prestigious CAREER program provides funding to early-career faculty to develop research and educational programs at their home institutions. If fully funded over five years, the grant will amount to $950,000.

Opher will use the grant for three specific projects: supporting the work of her two graduate students, as well as a postdoctoral student; developing a three-year summer school in space plasma physics; and hosting a summer roundtable that would assist women starting science careers by providing advice on funding, networking, and professional skills.

Working with women scientists is something that’s especially a passion for Opher that is being fulfilled at Mason. Not only does the Physics and Astronomy Department at Mason have an unusually high percentage of women professors, but it has seen an increase in female students as well.

And for Opher, sharing career tips with other women scientists extends to her own family. Her fraternal twin sister won a CAREER award in 2005 for work using nanotechnology to manipulate the way light flows over silicon chips. Opher says she asked to look at her sister’s NSF proposal for hints on how to craft one successfully. The Mason scientist clearly picked up some good pointers. She was also nominated for a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE), the top U.S. government honor for up-and-coming researchers. Each year, NSF selects nominees for PECASE from among the most meritorious new CAREER awardees.

With all these new discoveries and the potential to heavily influence the way the solar system is studied in the future, it’s no wonder that Opher is excited about her career.

“We’ve never had an idea of what our backyard looked like, and now we have a chance,” she says. “Nature is trying to tell us something, and it’s really neat to get to listen.”

Editor’s note: Karen Akerlof also contributed to this story.